If a parasite sucks the blood out of your tongue until it atrophies, and then becomes your tongue,

who, then, is doing the talking?

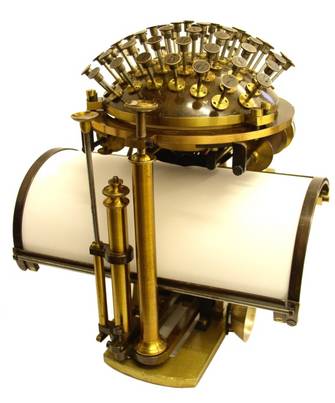

Cymothoa exigua, the tongue-eating louse

Historically, unreliable narrators have been somewhat less gruesome - more classic and captivating - Holden Caufield, Humbert Humbert, Huckleberry Finn (...though there is Alex in A Clockwork Orange). The term was coined by Wayne C. Booth in his 1961 The Rhetoric of Fiction, and its definition includes unreliability due to: ignorance, bias, psychological instability, self-deception, lack of worldliness, or deliberate deceit. It is a popular trope in post-modern literature and film, and because of its hip-ness reactions range from "it's way over-used and the effect is over-produced," to "it's a true representation of the range of selves within every human."

The idea is intriguing - knowingly spending time with someone who is lying to you, allowing them to tell you their story. The one-sidedness of reading a book or watching a movie provides the right dynamic for this. You, on a comfortable couch, the perfect receptacle. The unreliable narrator, cozily embedded in their medium, the scoundrel you can safely love.

You can bound across a field of flowers into the situation because, dear reader, the unreliable narrator is

reliably unreliable. Suspend disbelief, celebrate your fraudulent counterpart, created by an author just for you. It's our favorite kind of OSLab opening. There's an agreed upon space of tension, and maybe a nervous sort of co-creativity. Whatever is happening is real, and not real.

It's all in good fun, so there's nothing to fear.

"I heard all things in the heaven and in the earth. I heard many things in hell. How, then, am I mad? Hearken! and observe how healthily – how calmly I can tell you the whole story.”